Finding what you expect is a common failing of human beings — however I doubt it is wishful thinking that’s got me finding confirmation of my expectations in the RBA’s Q1’14 SOMP.

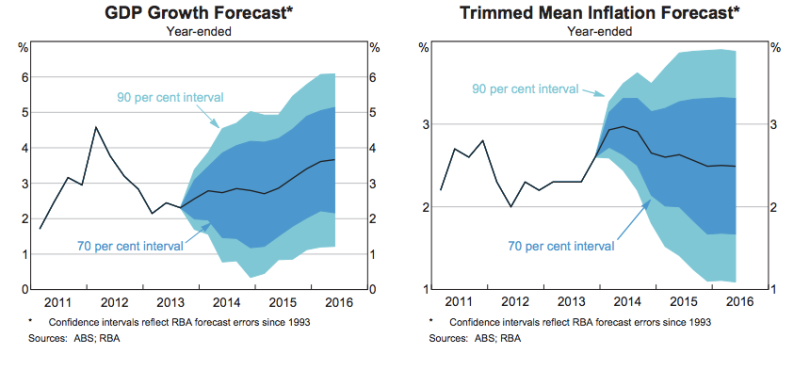

As ever, the place to start with is the last page. Assuming the cash rate is unchanged at 2.5% until mid 2016, that the nominal AUD is steady at 89c (v the USD or a TWI of 69), and that the price of (Brent) Crude Oil is stable at USD104/bbl, the RBA expects that growth will be sub-trend until mid-2015, and that inflation will return to 2.5% over the projection period.

Of course, they would say that, else they’d be contemplating rate hikes — but within the confines of the forecasts this set of projections is consistent with the RBA holding the cash rate steady at 2.5% deep into 2015. Assuming these forecasts are correct, the RBA is likely to respond to above trend growth in H2’15 by raising rates (to keep inflation around 2.5% in 2016) — demand responds to rates with a lag, and inflation responds demand with a lag, so they need to move early to keep inflation in check.

Before moving forward to my own view of the risks, it’s worth emphasising the dominant role of the AUD’s depreciation in these forecast revisions. Basically all the (modest) improvement in demand is from the weaker currency.

This outlook is a little stronger than it was at the time of the November Statement, primarily owing to the lower exchange rate, which is expected to boost exports and restrain imports (to the benefit of domestic production). The outlook for the various components of domestic demand is little changed

It follows that if AUD goes back up to where it was for the Q4’13 SOMP (AUDUSD 95c & TWI at 72) demand growth will drop back to the softer Q4’13 SOMP forecast; consequently inflation will decline faster, and the RBA’s easing bias may be re-instated.

What about inflation? Well like everyone else the RBA is a little confused by the Q4’13 inflation data. They put forth three explanations: faster FX passthrough, noise, and a supply-side collapse. I believe the first and second — it’s hard to square the supply-side story with the soft labour market (note that the RBA was also surprised by the weakness of wag growth).

The inflation forecasts have been revised higher in the short term, reflecting a combination of the lower exchange rate and the higher-than-expected December quarter CPI outcome, which have more than offset the effect of the softer outlook for wage growth.

In the context of a decline in the terms of trade (which means the equilibrium value of the AUD is lower) and a weak labour market, the RBA should look through the first stage impact of the weaker AUD: according to the RBA the lower AUD added ~50bps to the core inflation forecast in both 2014 and 2015.

Subtracting the consequences of the lower level of the AUD, we get an ex-FX core inflation forecast of ~2.25% for 2014, and ~2% for 2015. Once this adjustment is made, it’s clear why the RBA expects to be on hold for an extended period: excluding what ought to be ignored, the inflation forecast remains below the RBA’s target of 2.5% across the cycle.

Of course figuring out what’s FX and what’s true inflation is tricky, so the RBA’s move to a neutral bias is prudent. The RBA has a track record of being cautious in the proximity of high inflation prints, so this behaviour was to be expected: the Nov’12 pause following a carbon-tax inflation print that was biased up by ~25bps is the most recent example (they cut in Dec’12 as demand data remained soft).

Even within the context of these forecasts, there are good reasons to doubt that we are going to see such high inflation prints. Foremost is that it’s highly likely that the carbon tax will be repealed in July 2014. This will reduce the core inflation projection from H2’14 to H2’15 by ~25bps (back to 2% to 3% -> bang on target).

This ought to keep the RBA comfortably neutral through to H2 2015.

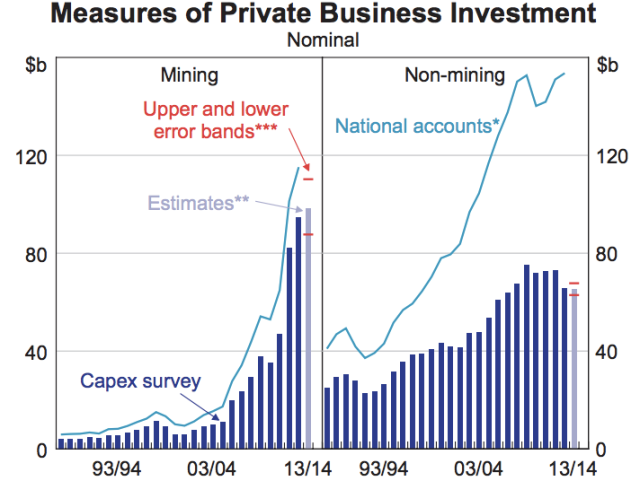

I see the risks around the RBA’s forecasts as to the downside. My judgement is that mining investment will fall away more quickly than the RBA expects, and I doubt that non-mining investment will be able to fill the gap: how could it? Mining capex is going to decline by ~40bn over the next few years, and non-mining is very unlikely to rise by that amount (if it occurred it would be an all time high by a large margin).

Sure, the economy will make a little back on net-exports, but unlikely enough to hit the RBA’s inflation forecasts. The problem is that project labour demand declines by between five sixths and two thirds as the projects move into the production phase.

Thus, while GDP will look okay, the labour market is likely to remain weak — and if the labour market is weak, we are unlikely to have a core inflation problem.

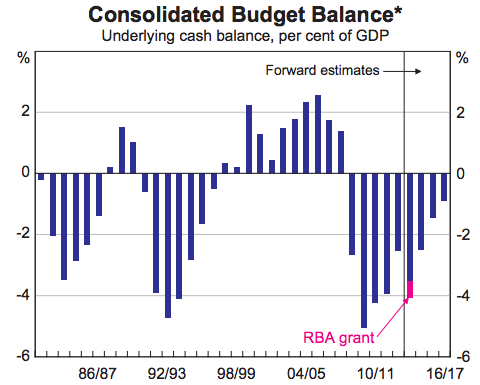

The other source of pressure to keep rates low is fiscal policy. As the RBA notes:

the budget projections continue to imply a pronounced fiscal consolidation over coming years …

… The fiscal consolidation foreshadowed by state and

federal governments implies the weakest period of

growth in public demand for at least 50 years

If i’m right about the downside risks from mining investment, then growth in public demand is likely to be even weaker. This follows, as a weak domestic economy means weak growth of public receipts: so that the required fiscal adjustment will be larger and take longer than currently expected. This ought to keep demand weak (and inflation low) over the projection period.

Additionally, my guess is that the newly elected federal government will tighten things up a little in their first budget (May 2014) — after all the RBA has 250bps to play with so there is basically no risk of causing a recession by tightening fiscal policy.

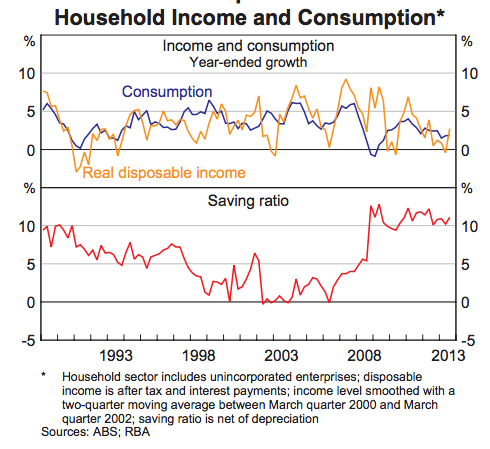

The thing that could make me wrong in all of this is if consumption bounced.

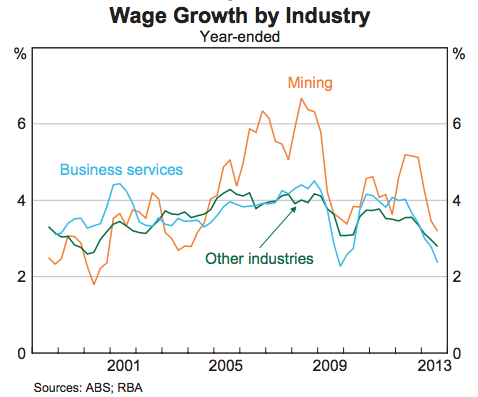

Most likely this would have to be funded by a decrease in the savings rate. Real disposable income growth is likely to remain diminished by weak wages growth (wage growth is at recessionary lows — see the below chart) and ongoing inflation in must-buy products like Utilities, Education, Health and Rent.

The boost in house prices is a key reason we might see the savings rate decline. Why save cash income when your assets are rising in value?

This sounds mad, but it has happened before — in the 2000s when house prices boomed, the associated withdrawal of equity saw households elect to cease saving from their regular income.

The reason i do not expect this to occur is that the labour market remains soft, and so job insecurity remains very high.

However, i am aware that is the weakest part of my argument. Australia enjoyed a soft economy and a drop in the savings rate in 2003 as housing boomed. If i’m wrong, this seems the most likely source of error.

Great work as always. So much better to wake up to this on Sunday morning than the lifestyle bumf in the papers.

I’ve been thinking for some time that the RBA needs to engineer a housing (investment) boom and a consumption boom to replace the mining investment boom. To me it makes perfect sense that if you want trend growth in GDP, and business investment and government spending are falling for reasons unrelated to the strength of demand, that the other components need to pick up somehow. And it is the RBA’s job to make sure they do. As a Gen-Xer, I look around and see Ys already seemingly spending everything they earn (was it ever thus?), perhaps explained by later and later family formation, which means that the behavioural changes towards saving we used to see in the mid-to-late 20s we now see in early-to-mid 30s. Gen Xers have some equity, but facing family commitments as they do, they are the ones probably most spooked by (if not most vulnerable to) the weak labour market. That leaves the In-betweeners and the Baby Boomers as the generations with equity and the willingness to deploy it given the right conditions. They’re currently in their 50s and 60s, so will be spending on restaurants, hairdressers, cleaners and travel for a while yet. Even the less well-heeled ones have plenty of housing equity and have scope to ramp up spending if they feel confident about house prices. At some stage, they will seek to help their offspring buy property. In the long run, perhaps the richness of one’s parents will determine whether an average Y’er lives inner-city or outer suburbia. Either way, this means the RBA can’t afford to puncture the house price boom for the foreseeable future, unless a strong global equity rally means that the olds don’t care so much about house prices. It’s hard to see that happening at this point, although could we get a Yellen-induced boost from a taper pause?

The media discussion about the role of unions in the building industry highlights another supply-side issue that needs to be fixed if we want affordable housing. I would love to see an Asian developer like Jaypee Greens enter the market like an international retailer and shake things up. By the sounds of it, they will need to come in a big way, with their own supply chains to by-pass the inefficiencies we see here.

Rajat, we already had our housing boom and our consumption boom, and they were all founded by the big credit boom… we can’t “boom” forever! We now have to work hard to repay the money we were advanced. We simply can’t repay the debt by taking on more and more debt. We have a debt to repay and I am sure we have used the money we borrowed to fund fantastic, productive investments, not for speculation. :)

My point is that if government is saving (or reducing its dissaving), then other things being equal (ie external sector), the private sector needs to dissave (or reduce its saving) to keep growth at trend. You can’t have both the private and public sectors saving and expect trend growth. Frankly, I would much prefer private borrowing and spending to replace public borrowing and spending.

Neither I think: a period of consolidation at current level must follow. That’s how you grow stronger and weed out the weak (= bad investments). We can’t constantly bail-out bad investments by injecting more money into the system.

Investment “boom” has happened and it’s going to be behind us soon:

/large

Now kids only able to buy houses with their parents help, in most European cities that’s already the case for a long time…. unless you want to live way out. They will not want to, so they will stay home for longer. great! :)

hmm a 3% Nominal GDP forecast both for this fiscal year and next year and you say there is little risk in tightening?

Are you from the Bundesbank?

tighten when nominal GDP growth gets to trend!

Apart from that you have essentially magnified my thoughts.

We both disagree with the Kouk!

Really good summary as I expected I might add

As ever, we have different views about fiscal multipliers.

You krauts have funny theories!!!

I have just given you a plug and backed you against the The Kouk!

I love the irony

The kouk HAWK,

Ricardian Ambivalence DOVE

I hope it doesn’t mean i am slow and he is quick!

Ricardo is back (it seems). Great stuff

FWIW, a good rap from Matt Cowgill:

I was wondering where all those twitter hits came from.

I know what you are doing: you are trying to keep me engaged in this project – it is working.

Ricardo, IMHO one of your best writing ever! Clear, concise and objective! Great work.

When (if!) the rate hikes will come, how many? Will we get 25bps or 50bps, before we resume rate cutting ?!?!?!? ha, ha :)

IMO demographics and international economic conditions are resetting the new neutral level of IR to very low, probably actually where we are now and should have been since after 2008.